- Static Fonts

- Smart Fonts

- Ligature

- Kerning

Font Format

A lot of tables in font file.

1 Glyphs (glyf):

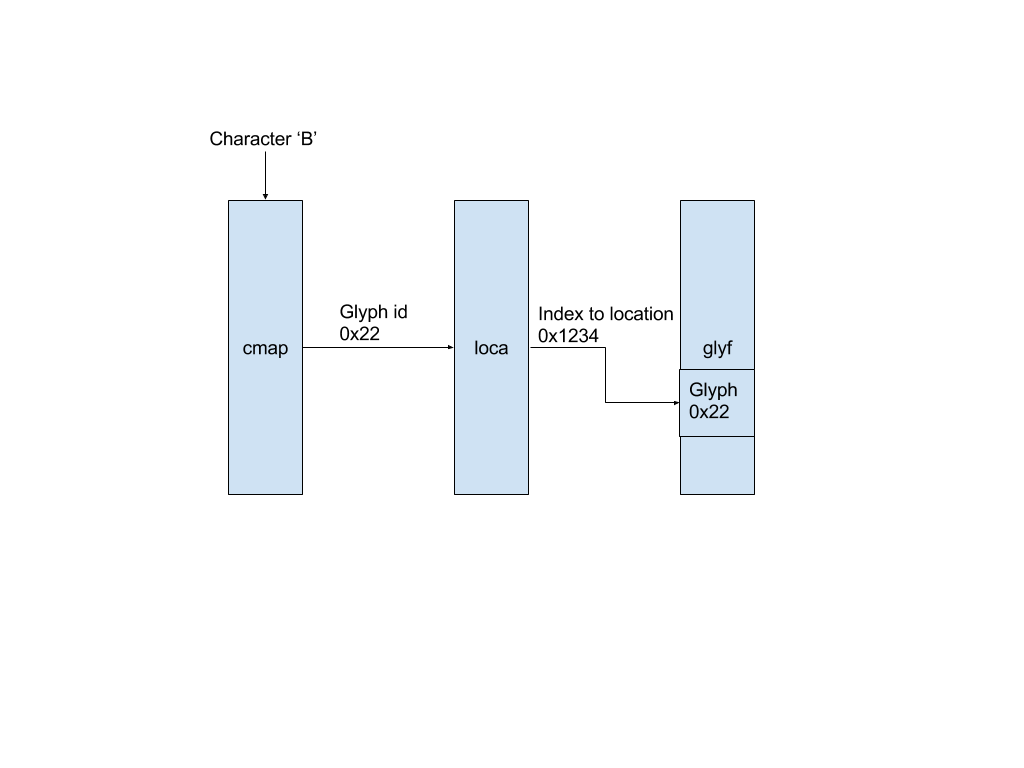

glyf table: glyph id -> glyph A particular glyph is identified by a glyph id, which is used exclusively throughout the font to identify that glyph.

Hinting:

The image on the left is a glyph rendered on a pixel screen without (or with poor) hinting. The Image on the right is with a good hinting.

cvt, fpgm, prep are three tables storing hinting information.

Anti-aliasing: is another approach which has become more popular recently. It consists of smudging the edges of the glyph outline slightly by using grey pixels on a screen. The eye averages out the smudging, and the results are clearer than without it. This approach is used in such programs as Adobe Acrobat Reader and for some fonts in Windows to produce more legible glyphs.

ClearType is introduced by Microsoft that is also known as subpixel. One white pixel consists of red, green and blue pixels placed very close together. ClearType manipulates these color pixels separately to finely control the edges of glyphs, resulting in cleaner, more legible letters.

2 Character to Glyph Mapping (cmap)

cmap: outside encoding -> glyph id.

cmap contains a set of mapping subtables for different technologies and architectures. For example, most TrueType fonts have three subtables within the ‘cmap’, two for Apple and one for Microsoft.

Each subtable has two numbers associated with it: the platform id and the encoding id. The platform id indicates what architecture the subtable is designed for.

platform id 0: Apple Unicode

platform id 1: Apple Script Manager

platform id 2: ISO

platform id 3: Microsoft

The meaning of the encoding id depends on the platform. For example, some older fonts have only two subtables: Platform 1, encoding 0 (Mac Roman 8-bit simple 256 glyph encoding) and Platform 3, encoding 1 (Windows Unicode).

Some reserved glyph id

| Glyph Id | Character |

| 0 | unknown glyph |

| 1 | null |

| 2 | carriage return |

| 3 | space |

3 Glyph Names (post)

The ‘post’ table provides a name for each glyph based on PostScript conventions. These names are primarily of interest to font designers, engineers, and automatic tools which work with fonts at the glyph level. The table also stores some miscellaneous information such as the italic angle, the underline position, and whether the font uses proportional spacing. It is possible (common in large CJK fonts) to have a ‘post’ table which is empty (provides no names.)

Glyph PostScript names can contain any alphanumeric character, though there are some restrictions. Adobe’s naming convention is the industry-wide standard. This provides a predefined list of 1054 special names, like .notdef, space, and Aacute. Glyphs not in this list are given a name based on their unicode value (e.g. uni0E4D) with a possible modifier (uni0E48.left) or based on a sequence of codes (for ligatures—uni0E380E48). If a font contains a non-empty ‘post’ table and does not use these naming guidelines, it may not work correctly with some software (e.g. Adobe Acrobat). For detailed information about PostScript glyph names, see ![]() http://partners.adobe.com/asn/developer/type/unicodegn.html.

http://partners.adobe.com/asn/developer/type/unicodegn.html.

4 Metrics, Style, Weight, etc. (hmtx, hdmx, OS/2, etc.)

hmtx: advance width and left side bearing for each glyph.

hdtx: (horizontal device metrics): precalculated advance widths and left side bearing for each glyph at various sizes and resolutions.

vmtx, vdmx: used for glyphs drawn on a vertical baseline. They are analagous to the hmtx and hdmx tables.

OS/2: font wide metrics like line spacing, style and weight, rough description of its overall look. It also contains what range of characters are in the font, both in terms of ‘Windows’ codepages and Unicode ranges.

head, hhea: used in mac OS to store info of OS/2 table in Windows. The info in all three tables should agree. head contains the checksum for the entire font and other summary information about the font as a whole. hhea table specifies summarize the info about the horizontal metrics.

The ‘hmtx’ (horizontal metrics) table specifies the advance width and left side bearing for each glyph. Glyphs are positioned relative to a given point on the screen or page. The horizontal distance from the current point to the left most point on the glyph is the left side bearing. The horizontal distance the current point moves after the glyph is drawn to be positioned for the next glyph is the advance width. For example, an overstriking glyph will have an advance width of 0 with possibly a negative left side bearing (if it is intended to follow the overstruck glyph), while a space glyph will have a large advance width, even though there is no actual glyph outline for this glyph.

Changing the advance width will alter the positioning of every glyph on a line after the changed glyph. Changing the left side bearing will only alter the placement of an individual glyph. In right to left scripts, glyphs still are described using a left to right coordinate system.

The left side bearing and advance width will scale along with the glyph outlines and also can be modified by hints. For performance reasons (e.g. calculating line breaks before actually rendering glyphs), a font may provide precalculated advance widths for each glyph at various sizes and resolutions in its ‘hdmx’ (horizontal device metrics) table.

To support glyphs drawn on a vertical baseline, the ‘vmtx’ and ‘VDMX’ tables may be present. They are analagous to the ‘hmtx’ and ‘hdmx’ tables.

The ‘OS/2’ table provides font wide metrics that control line spacing in Windows. It also indicates the style and weight of a font as well as a rough description of its overall look. On the Mac OS, the ‘head’ and ‘hhea’ tables are used instead of the ‘OS/2’ table to store this information. Information in all three tables should agree.

In addition, the ‘OS/2’ table provides information about what range of characters are in the font, both in terms of Windows’ codepages and Unicode ranges. This data can affect whether a given font will be used to display Unicode data. The ‘head’ table contains the checksum for the entire font and other summary information about the font as a whole. The ‘hhea’ table specifies summary information about the horizontal metrics.

5 Kerning (‘kern’)

The optional ‘kern’ table specifies how glyph combinations should be kerned. On the Windows, the only format which is supported provides simple pair kerning. Pairs of glyph ids are listed with the amount by which the origin of the second glyph should be moved in relation to the first glyph. This movement will result in a shift in all following glyphs on the same line. For example, if an ‘A’ follows a ‘W’ then the ‘A’ and all subsequent glyphs on the line should be moved left. OpenType and AAT tables provide a much more sophisticated mechanism that includes complex contextual kerning. For more information, see the relevant specification.

6 General Font Information (‘name’)

The ‘name’ table stores text strings which an application can use to provide information about the font. Each string in the ‘name’ table has a platform and encoding id corresponding to the platform and encoding ids in the ‘cmap’ table. Each string also has a language id which can be used to support strings in different languages. For Windows (platform id 3) the language id is the same as a Windows LCID. For the Mac OS (platform id 1), script manager codes are used instead. See the TrueType documentation for details.

Each string also has a name id which describes the meaning of this string and its use. The list below was taken from current documentation. This list may grow in the future. Other strings can be included but are not assigned a special meaning.

| Name Id | Meaning |

| 0 | Copyright notice |

| 1 | Font Family name. |

| 2 | Font Subfamily name. Font style (italic, oblique) and weight (light, bold, black, etc.). A font with no particular differences in weight or style (e.g. medium weight, not italic) should have the string “Regular” stored in this position. |

| 3 | Unique font identifier. Usually similar to 4 but with enough additional information to be globally unique. Often includes information from Id 8 and Id 0. |

| 4 | Full font name. This should be a combination of strings 1 and 2. Exception: if the font is “Regular” as indicated in string 2, then use only the family name contained in string 1. This is the font name that Windows will expose to users. |

| 5 | Version string. Must begin with the syntax ‘Version n.nn ‘ (upper case, lower case, or mixed, with a space following the number). |

| 6 | Postscript name for the font. |

| 7 | Trademark. Used to save any trademark notice/information for this font. Such information should be based on legal advice. This is distinctly separate from the copyright. |

| 8 | Manufacturer Name. |

| 9 | Designer. Name of the designer of the typeface. |

| 10 | Description. Description of the typeface. Can contain revision information, usage recommendations, history, features, etc. |

| 11 | URL Vendor. URL of font vendor (with protocol, e.g., http://, ftp://). If a unique serial number is embedded in the URL, it can be used to register the font. |

| 12 | URL Designer. URL of typeface designer (with protocol, e.g., http://, ftp://). |

| 13 | License description. Description of how the font may be legally used, or different example scenarios for licensed use. This field should be written in plain language, not legalese. |

| 14 | License information URL. Where additional licensing information can be found. |

| 15 | Reserved; Set to zero. |

| 16 | Preferred Family (Windows only). In Windows, the Family name is displayed in the font menu. The Subfamily name is presented as the Style name. For historical reasons, font families have contained a maximum of four styles, but font designers may group more than four fonts to a single family. The Preferred Family and Preferred Subfamily IDs allow font designers to include the preferred family/subfamily groupings. These IDs are only present if they are different from IDs 1 and 2. |

| 17 | Preferred Subfamily (Windows only). See above. |

| 18 | Compatible Full (Mac OS only). On the Mac OS, the menu name is constructed using the FOND resource. This usually matches the Full Name. If you want the name of the font to appear differently than the Full Name, you can insert the Compatible Full Name here. |

| 19 | Sample text. This can be the font name, or any other text that the designer thinks is the best sample text to show what the font looks like. |

| 20 | PostScript CID findfont name. |

| 21-255 | Reserved for future expansion. |

| 256-32767 | Font-specific names. |

7 What’s Left?

Four other tables are usually present in each font. The ‘loca’ table simply provides an offset (based on a glyph id) for glyph data in the ‘glyf’ table. It is required if a ‘glyf’ table is present (see below). The required ‘maxp’ table provides information about the overall complexity of the glyphs and hints. The optional ‘LTSH’ table indicates when a given glyph’s size begins to scale without being affected by hinting. The optional ‘PCLT’ table stores fontwide information based on Hewlett-Packard’s Printer Control Language specification.

Several other optional tables can be present which are used to accommodate bitmaps. An OpenType font can use the ‘CFF’ table (instead of the ‘glyf’ and ‘loca’ tables) for PostScript glyphs. OpenType, AAT, and Graphite also define additional tables primarily for smart rendering. Periodically entirely new tables or new fields within existing tables are added to the specification to support new rendering features.

Two other related though older font specifications that the reader should be aware of are TrueType Open and TrueType GX. Roughly, TrueType Open is like OpenType without the support for PostScript glyphs. TrueType GX is like AAT before support for Unicode was added.

8 Conclusion

In this section the reader has obtained a basic understanding of bare TrueType fonts and has been equipped to explore further. The official specifications (referenced in the Introduction) can provide more details. It is often helpful to compare specifications from both Microsoft and Apple.

To further explore smart rendering, “Rendering technologies overview” should be a useful resource. A quick summary of all tables used in TrueType, OpenType, AAT, and Graphite fonts can be found in TrueType table listing. For a better understanding of how rendering relates to keyboarding and encoding, see Constable (2000).

9 References

Constable, Peter. 2000. Understanding Multilingual software on MS Windows: The answer to the ultimate question of fonts, keyboards and everything. ms. Available in CTC Resource Collection 2000 CD-ROM, by SIL International. Dallas: SIL International.

Reference: http://graphite.sil.org/cms/scripts/page.php?site_id=nrsi&id=IWS-Chapter08

10. GSUB Table

1 to 1 substitution

1 to many substitution

glyph decomposition

many to 1 substitution

ligature

Language system is a sub-domain of script. For example, in the Cyrillic script, the Serbian language system always renders certain glyphs differently than the Russian language system.